The Changing Face of Distribution Marketing to Seniors

I’ve noticed a funny trend among marketers. We tend to talk about younger consumers in terms of their generation—for example, the term “millennials” has been a stand-in for a nyone under 35 for what seems like a decade or more—seniors are always seniors. I imagine this is due to some collective failure of imagination, whereby anyone under 50 can’t imagine a 65- or 70-year old as anything other than their parents or grandparents at that age.

Another way to put this is that for some marketers, the senior segment remains frozen in time. 65-year-olds in 2005 didn’t have smartphones and were wary of e-commerce; therefore, seniors in 2019 must be the same. However, it’s easy to forget that these consumers were in the prime of their careers in 2005, and, last I checked, by 2005 most white-collar workers were spending eight hours a day in front of laptop screens.

The same goes for social media. While I hear many marketers using the shorthand correlation that social media targeting should be inversely correlated with age, the data don’t bear this out. While platform use differs dramatically between those born in 1995 and 1965, as of mid-2019 social media use does not. It’s true that older consumers tend to use Facebook while younger consumers tend to use Instagram, but social media usage is, if anything, more prevalent among older consumers for certain use cases—like getting news and communicating between friends.

When it comes to e-commerce, “rising seniors” have had 20 years to get used to secure e-commerce pages—specifically the little lock that appears on secure sites—and spent 20 years before that giving their credit card information out over the telephone. The idea that seniors will hesitate to conduct business online is at this point probably more of a stereotype than reality.

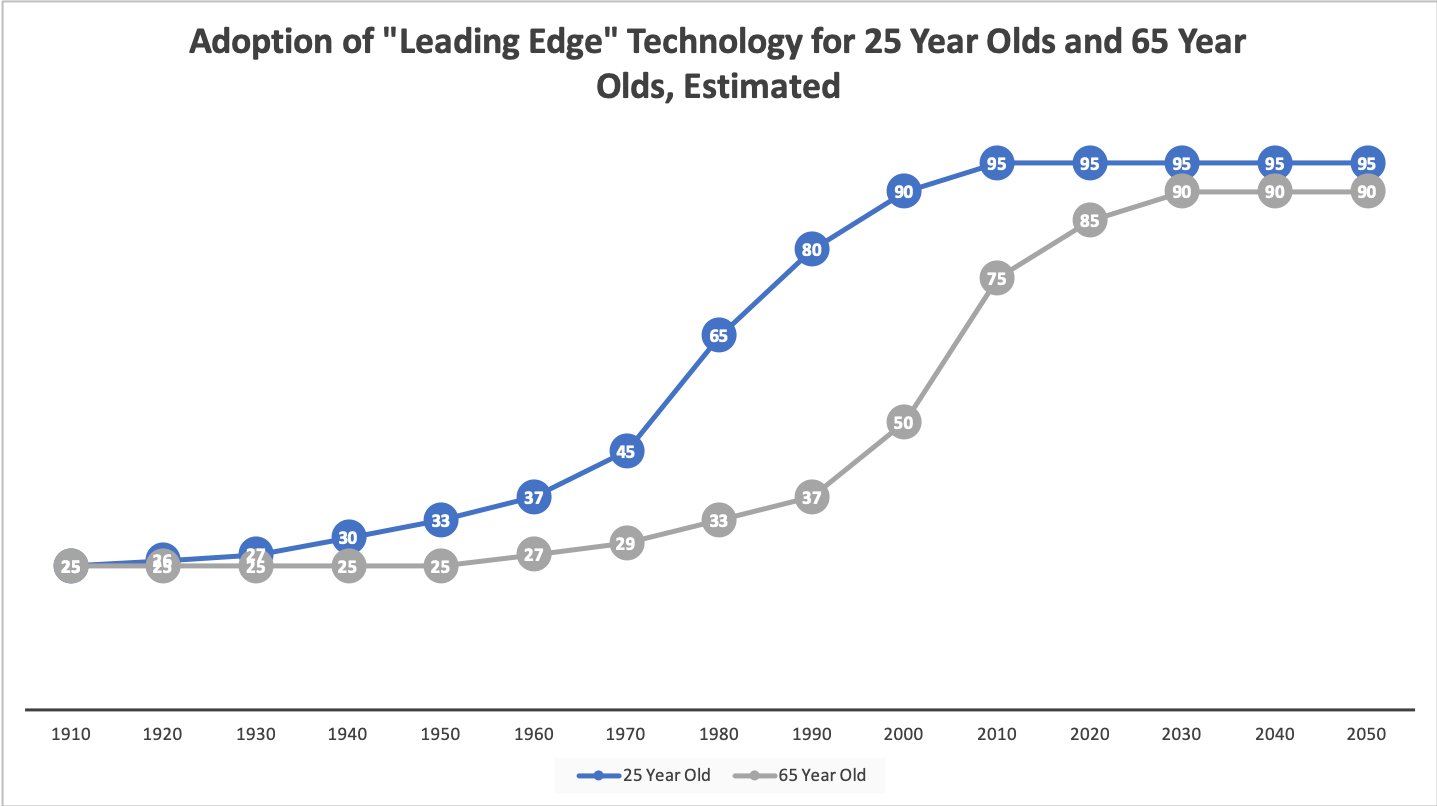

The hypothesis that I’m posing for marketers is that we are coming off a period of “maximum generational technology adoption difference”, and that the generational technology gap will begin to narrow again—potentially very quickly. Viewed across the long arc of history, the period between 1980 and 2010 was simply unprecedented when it came to the difference in technology understanding and adoption across age cohorts—and this difference is now rapidly declining.

To prove my point, in the chart below I’ve laid out an estimated adoption of “advanced technology” by generation, from around 1910 to today. In 1920, advanced technology was a car; in 1950 it was television; in 1970 maybe a dishwasher. For each of those points, there was a difference between the older and younger generations, but it wasn’t anywhere near as large as it was from 1970 to 2010. Two factors were at play in this relatively narrow gap.

First, the technological innovations of the early part of the 20th century were very expensive, big-ticket items. A Fort Model T—even though made for “everyman”—was still $850 when first introduced, around double the average salary for a worker at the time. This would be the equivalent of the cheapest car on the market today being something like $60,000. Even after the price fell to $300 by 1920, this was still a big lift for a typical family. Thus, young families were hard-pressed to adopt technological innovations, whether they wanted to or not. In other words, income was a much more limiting factor when it came to technology adoption than age was.

Secondly, much of the technological innovation of the early 20th century focused on work, domestic or otherwise. These were productivity inventions. The dishwasher, refrigerator, washing machine, and even the family car were designed to free up time, not to waste it. This meant that benefits were readily apparent and understandable to people who were working—in other words, those roughly 18 years old and up. The products were also less abstract and more straightforward. A refrigerator is an icebox that doesn’t need ice. A dishwasher means you don’t have to wash dishes in the sink.

Both of these factors changed practically overnight with the digital technology revolution. Because technology was based first on digital transistors (a lot cheaper than machined metal) and then later on software code (fixed cost intellectual property), kids could afford it. All of a sudden, age became the primary limiting factor in new technology adoption.

Personal computers were an early case in point. While the first computers were expensive–$3,600 for an Apple 2 on launch—this was still something like 10% of the average American’s income. And, within ten years, an IBM clone could be had for less than $1,000. Today, laptops are literally everywhere and practically free. I just checked on eBay and it’s possible to get a refurbished Toshiba that will do all basic “office” tasks for $54.

Getting specific, according to Pew Internet Research, 53% of 65+ Americans owned a smartphone as of February 2019, which is as high as the total smartphone penetration was at the end of 2012. What’s even more impressive is that the next age group down (50-64) is at a 79% penetration—2 points below the total U.S. 18+ population smartphone penetration. It’s hard to find time series data on technology adoption by age, but this feels like a much faster gap closing than, for example, PC adoption in the 1980s and 1990s.

Getting back to my original argument, it seems to me that marketers are forgetting that many of today’s age-in seniors are in fact technology experts, not neophytes. Sure, they are, on average, less capable with technology than 25-year-olds, but I’d argue that most of the difference lies in attitude towards technology, not in understanding. Using a TV analogy, we’re probably getting back to the point where we should be targeting based on dayparts and shows—not on television vs. print.

In other words, marketers should look at different creative treatments, language, and digital platforms when talking to seniors—but should absolutely be starting to look at “digital-first” for rising seniors. Companies that understand this and get on board quickly are almost guaranteed to win the hearts and minds of the always-important senior generation.

What will the future hold for intergenerational technology difference? Will there be an equivalent to the digital revolution of the 1980s-2000s that so radically separated generations? For the time being, it seems like most change is evolutionary, not revolutionary. Younger consumers are spending more time gaming, watching streaming video, and sending memes than older consumers—but they’re using the same tech to do it. There very well may be a “next big thing” that lengthens the technology gap between generations, but for the foreseeable future, we’ll return to style over function when it comes to targeting by age.